Designing a schema for observability

We recommend users always create their own schema for logs and traces for the following reasons:

- Choosing a primary key - The default schemas use an

ORDER BYwhich is optimized for specific access patterns. It is unlikely your access patterns will align with this. - Extracting structure - Users may wish to extract new columns from the existing columns e.g. the

Bodycolumn. This can be done using materialized columns (and materialized views in more complex cases). This requires schema changes. - Optimizing Maps - The default schemas use the Map type for the storage of attributes. These columns allow the storage of arbitrary metadata. While an essential capability, as metadata from events is often not defined up front and therefore can't otherwise be stored in a strongly typed database like ClickHouse, access to the map keys and their values is not as efficient as access to a normal column. We address this by modifying the schema and ensuring the most commonly accessed map keys are top-level columns - see "Extracting structure with SQL". This requires a schema change.

- Simplify map key access - Accessing keys in maps requires a more verbose syntax. Users can mitigate this with aliases. See "Using Aliases" to simplify queries.

- Secondary indices - The default schema uses secondary indices for speeding up access to Maps and accelerating text queries. These are typically not required and incur additional disk space. They can be used but should be tested to ensure they are required. See "Secondary / Data Skipping indices".

- Using Codecs - Users may wish to customize codecs for columns if they understand the anticipated data and have evidence this improves compression.

We describe each of the above use cases in detail below.

Important: While users are encouraged to extend and modify their schema to achieve optimal compression and query performance, they should adhere to the OTel schema naming for core columns where possible. The ClickHouse Grafana plugin assumes the existence of some basic OTel columns to assist with query building e.g. Timestamp and SeverityText. The required columns for logs and traces are documented here [1][2] andhere, respectively. You can choose to change these column names, overriding the defaults in the plugin configuration.

Extracting structure with SQL

Whether ingesting structured or unstructured logs, users often need the ability to:

- Extract columns from string blobs. Querying these will be faster than using string operations at query time.

- Extract keys from maps. The default schema places arbitrary attributes into columns of the Map type. This type provides a schema-less capability that has the advantage of users not needing to pre-define the columns for attributes when defining logs and traces - often, this is impossible when collecting logs from Kubernetes and wanting to ensure pod labels are retained for later search. Accessing map keys and their values is slower than querying on normal ClickHouse columns. Extracting keys from maps to root table columns is, therefore, often desirable.

Consider the following queries:

Suppose we wish to count which URL paths receive the most POST requests using the structured logs. The JSON blob is stored within the Body column as a String. Additionally, it may also be stored in the LogAttributes column as a Map(String, String) if the user has enabled the json_parser in the collector.

SELECT LogAttributes

FROM otel_logs

LIMIT 1

FORMAT Vertical

Row 1:

──────

Body: {"remote_addr":"54.36.149.41","remote_user":"-","run_time":"0","time_local":"2019-01-22 00:26:14.000","request_type":"GET","request_path":"\/filter\/27|13 ,27| 5 ,p53","request_protocol":"HTTP\/1.1","status":"200","size":"30577","referer":"-","user_agent":"Mozilla\/5.0 (compatible; AhrefsBot\/6.1; +http:\/\/ahrefs.com\/robot\/)"}

LogAttributes: {'status':'200','log.file.name':'access-structured.log','request_protocol':'HTTP/1.1','run_time':'0','time_local':'2019-01-22 00:26:14.000','size':'30577','user_agent':'Mozilla/5.0 (compatible; AhrefsBot/6.1; +http://ahrefs.com/robot/)','referer':'-','remote_user':'-','request_type':'GET','request_path':'/filter/27|13 ,27| 5 ,p53','remote_addr':'54.36.149.41'}

Assuming the LogAttributes is available, the query to count which URL paths of the site receive the most POST requests:

SELECT path(LogAttributes['request_path']) AS path, count() AS c

FROM otel_logs

WHERE ((LogAttributes['request_type']) = 'POST')

GROUP BY path

ORDER BY c DESC

LIMIT 5

┌─path─────────────────────┬─────c─┐

│ /m/updateVariation │ 12182 │

│ /site/productCard │ 11080 │

│ /site/productPrice │ 10876 │

│ /site/productModelImages │ 10866 │

│ /site/productAdditives │ 10866 │

└──────────────────────────┴───────┘

5 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.735 sec. Processed 10.36 million rows, 4.65 GB (14.10 million rows/s., 6.32 GB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 153.71 MiB.

Note the use of the map syntax here e.g. LogAttributes['request_path'], and the path function for stripping query parameters from the URL.

If the user has not enabled JSON parsing in the collector, then LogAttributes will be empty, forcing us to use JSON functions to extract the columns from the String Body.

We generally recommend users perform JSON parsing in ClickHouse of structured logs. We are confident ClickHouse is the fastest JSON parsing implementation. However, we recognize users may wish to send logs to other sources and not have this logic reside in SQL.

SELECT path(JSONExtractString(Body, 'request_path')) AS path, count() AS c

FROM otel_logs

WHERE JSONExtractString(Body, 'request_type') = 'POST'

GROUP BY path

ORDER BY c DESC

LIMIT 5

┌─path─────────────────────┬─────c─┐

│ /m/updateVariation │ 12182 │

│ /site/productCard │ 11080 │

│ /site/productPrice │ 10876 │

│ /site/productAdditives │ 10866 │

│ /site/productModelImages │ 10866 │

└──────────────────────────┴───────┘

5 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.668 sec. Processed 10.37 million rows, 5.13 GB (15.52 million rows/s., 7.68 GB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 172.30 MiB.

Now consider the same for unstructured logs:

SELECT Body, LogAttributes

FROM otel_logs

LIMIT 1

FORMAT Vertical

Row 1:

──────

Body: 151.233.185.144 - - [22/Jan/2019:19:08:54 +0330] "GET /image/105/brand HTTP/1.1" 200 2653 "https://www.zanbil.ir/filter/b43,p56" "Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 6.1) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/71.0.3578.98 Safari/537.36" "-"

LogAttributes: {'log.file.name':'access-unstructured.log'}

A similar query for the unstructured logs requires the use of regular expressions via the extractAllGroupsVertical function.

SELECT

path((groups[1])[2]) AS path,

count() AS c

FROM

(

SELECT extractAllGroupsVertical(Body, '(\\w+)\\s([^\\s]+)\\sHTTP/\\d\\.\\d') AS groups

FROM otel_logs

WHERE ((groups[1])[1]) = 'POST'

)

GROUP BY path

ORDER BY c DESC

LIMIT 5

┌─path─────────────────────┬─────c─┐

│ /m/updateVariation │ 12182 │

│ /site/productCard │ 11080 │

│ /site/productPrice │ 10876 │

│ /site/productModelImages │ 10866 │

│ /site/productAdditives │ 10866 │

└──────────────────────────┴───────┘

5 rows in set. Elapsed: 1.953 sec. Processed 10.37 million rows, 3.59 GB (5.31 million rows/s., 1.84 GB/s.)

The increased complexity and cost of queries for parsing unstructured logs (notice performance difference) is where we recommend users always use structured logs where possible.

The above query could be optimized to exploit regular expression dictionaries. See "Using Dictionaries" for more detail.

Both of these use cases can be satisfied using ClickHouse by moving the above query logic to insert time. We explore several approaches below, highlighting when each is appropriate.

Users may also perform processing using OTel Collector processors and operators as described here. In most cases, users will find ClickHouse is significantly more resource-efficient and faster than the collector's processors. The principal downside of performing all event processing in SQL is the coupling of your solution to ClickHouse. For example, users may wish to send processed logs to alternative destinations from the OTel collector e.g. S3.

Materialized columns Materialized columns offer the simplest solution to extract structure from other columns. Values of such columns are always calculated at insert time and cannot be specified in INSERT queries.

Materialized columns incur additional storage overhead as the values are extracted to new columns on disk at insert time.

Materialized columns support any ClickHouse expression and can exploit any of the analytical functions for processing strings (including regex and searching) and urls, performing type conversions, extracting values from JSON or mathematical operations.

We recommend materialized columns for basic processing. They are especially useful for extracting values from maps, promoting them to root columns, and performing type conversions. They are often most useful when used in very basic schemas or in conjunction with materialized views. Consider the following schema for logs from which the JSON has been extracted to the LogAttributes column by the collector:

CREATE TABLE otel_logs

(

`Timestamp` DateTime64(9) CODEC(Delta(8), ZSTD(1)),

`TraceId` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`SpanId` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`TraceFlags` UInt32 CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`SeverityText` LowCardinality(String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`SeverityNumber` Int32 CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ServiceName` LowCardinality(String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`Body` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ResourceSchemaUrl` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ResourceAttributes` Map(LowCardinality(String), String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ScopeSchemaUrl` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ScopeName` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ScopeVersion` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ScopeAttributes` Map(LowCardinality(String), String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`LogAttributes` Map(LowCardinality(String), String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`RequestPage` String MATERIALIZED path(LogAttributes['request_path']),

`RequestType` LowCardinality(String) MATERIALIZED LogAttributes['request_type'],

`RefererDomain` String MATERIALIZED domain(LogAttributes['referer'])

)

ENGINE = MergeTree

PARTITION BY toDate(Timestamp)

ORDER BY (ServiceName, SeverityText, toUnixTimestamp(Timestamp), TraceId)

The equivalent schema for extracting using JSON functions from a String Body can be found here.

Our three materialized view columns extract the request page, request type, and referrer's domain. These access the map keys and apply functions to their values. Our subsequent query is significantly faster:

SELECT RequestPage AS path, count() AS c

FROM otel_logs

WHERE RequestType = 'POST'

GROUP BY path

ORDER BY c DESC

LIMIT 5

┌─path─────────────────────┬─────c─┐

│ /m/updateVariation │ 12182 │

│ /site/productCard │ 11080 │

│ /site/productPrice │ 10876 │

│ /site/productAdditives │ 10866 │

│ /site/productModelImages │ 10866 │

└──────────────────────────┴───────┘

5 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.173 sec. Processed 10.37 million rows, 418.03 MB (60.07 million rows/s., 2.42 GB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 3.16 MiB.

Materialized columns will, by default, not be returned in a

SELECT *. This is to preserve the invariant that the result of a SELECT * can always be inserted back into the table using INSERT. This behavior can be disabled by settingasterisk_include_materialized_columns=1and can be enabled in Grafana (seeAdditional Settings -> Custom Settingsin data source configuration).

Materialized views

Materialized views provide a more powerful means of applying SQL filtering and transformations to logs and traces.

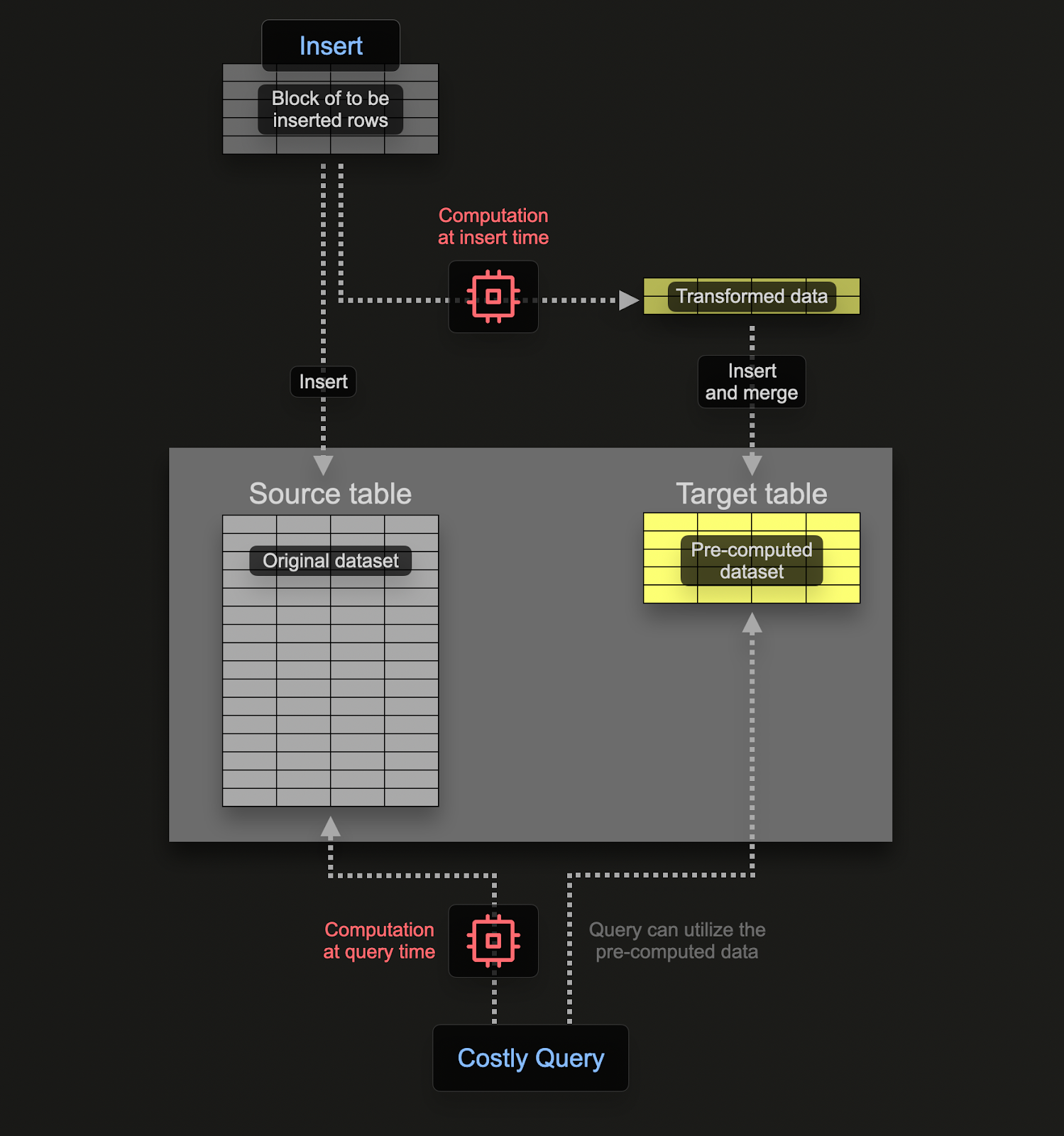

Materialized Views allow users to shift the cost of computation from query time to insert time. A ClickHouse Materialized View is just a trigger that runs a query on blocks of data as they are inserted into a table. The results of this query are inserted into a second "target" table.

Materialized views in ClickHouse are updated in real time as data flows into the table they are based on, functioning more like continually updating indexes. In contrast, in other databases materialized views are typically static snapshots of a query that must be refreshed (similar to ClickHouse Refreshable Materialized Views).

The query associated with the materialized view can theoretically be any query, including an aggregation although limitations exist with Joins. For the transformations and filtering workloads required for logs and traces, users can consider any SELECT statement to be possible.

Users should remember the query is just a trigger executing over the rows being inserted into a table (the source table), with the results sent to a new table (the target table).

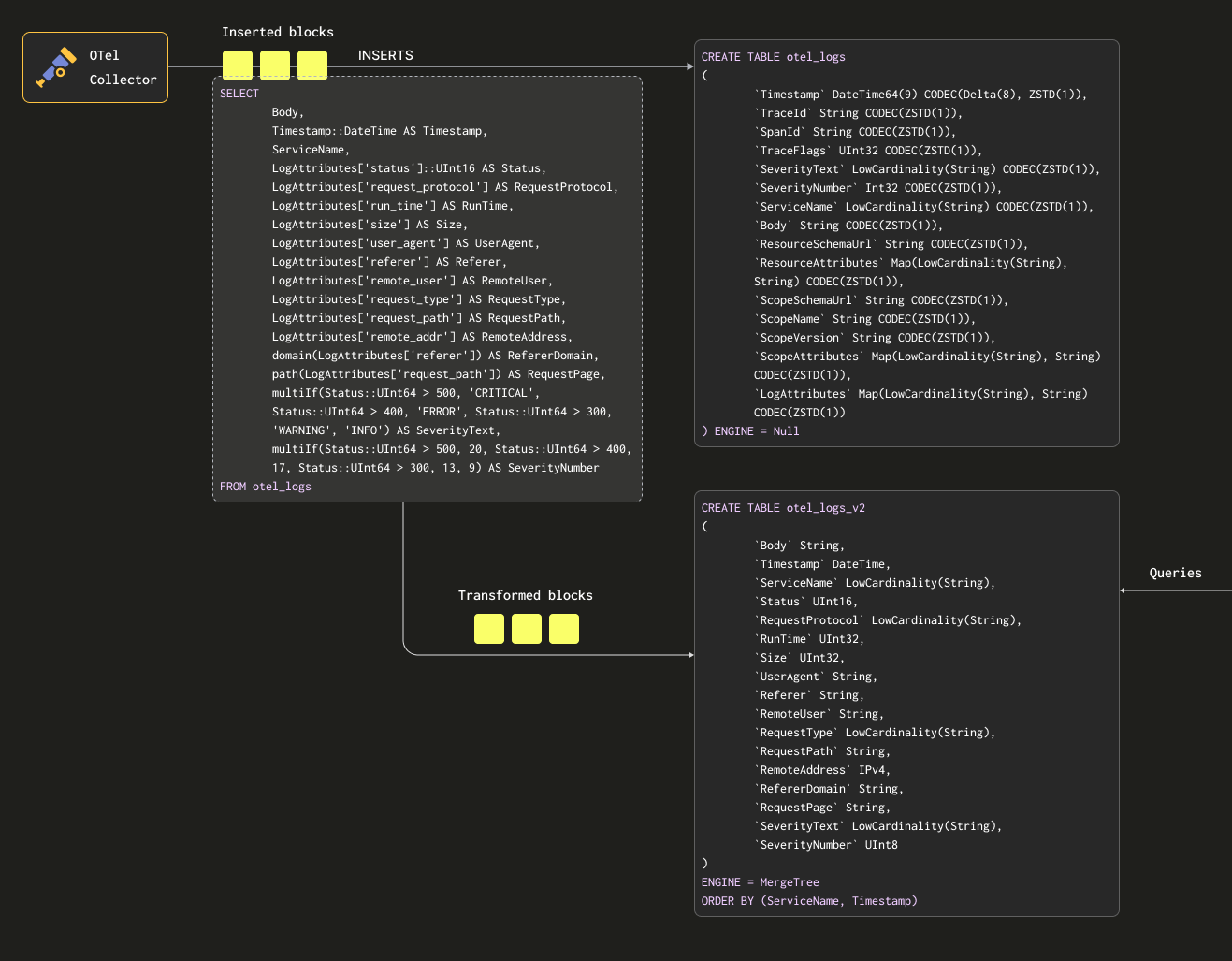

In order to ensure we don't persist the data twice (in the source and target tables) we can change the table of the source table to be a Null table engine, preserving the original schema. Our OTel collectors will continue to send data to this table. For example, for logs, the otel_logs table becomes:

CREATE TABLE otel_logs

(

`Timestamp` DateTime64(9) CODEC(Delta(8), ZSTD(1)),

`TraceId` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`SpanId` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`TraceFlags` UInt32 CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`SeverityText` LowCardinality(String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`SeverityNumber` Int32 CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ServiceName` LowCardinality(String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`Body` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ResourceSchemaUrl` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ResourceAttributes` Map(LowCardinality(String), String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ScopeSchemaUrl` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ScopeName` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ScopeVersion` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ScopeAttributes` Map(LowCardinality(String), String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`LogAttributes` Map(LowCardinality(String), String) CODEC(ZSTD(1))

) ENGINE = Null

The Null table engine is a powerful optimization - think of it as /dev/null. This table will not store any data, but any attached materialized views will still be executed over inserted rows before they are discarded.

Consider the following query. This transforms our rows into a format we wish to preserve, extracting all columns from LogAttributes (we assume this has been set by the collector using the json_parser operator), setting the SeverityText and SeverityNumber (based on some simple conditions and definition of these columns). In this case we also only select the columns we know will be populated - ignoring columns such as the TraceId, SpanId and TraceFlags.

SELECT

Body,

Timestamp::DateTime AS Timestamp,

ServiceName,

LogAttributes['status'] AS Status,

LogAttributes['request_protocol'] AS RequestProtocol,

LogAttributes['run_time'] AS RunTime,

LogAttributes['size'] AS Size,

LogAttributes['user_agent'] AS UserAgent,

LogAttributes['referer'] AS Referer,

LogAttributes['remote_user'] AS RemoteUser,

LogAttributes['request_type'] AS RequestType,

LogAttributes['request_path'] AS RequestPath,

LogAttributes['remote_addr'] AS RemoteAddr,

domain(LogAttributes['referer']) AS RefererDomain,

path(LogAttributes['request_path']) AS RequestPage,

multiIf(Status::UInt64 > 500, 'CRITICAL', Status::UInt64 > 400, 'ERROR', Status::UInt64 > 300, 'WARNING', 'INFO') AS SeverityText,

multiIf(Status::UInt64 > 500, 20, Status::UInt64 > 400, 17, Status::UInt64 > 300, 13, 9) AS SeverityNumber

FROM otel_logs

LIMIT 1

FORMAT Vertical

Row 1:

──────

Body: {"remote_addr":"54.36.149.41","remote_user":"-","run_time":"0","time_local":"2019-01-22 00:26:14.000","request_type":"GET","request_path":"\/filter\/27|13 ,27| 5 ,p53","request_protocol":"HTTP\/1.1","status":"200","size":"30577","referer":"-","user_agent":"Mozilla\/5.0 (compatible; AhrefsBot\/6.1; +http:\/\/ahrefs.com\/robot\/)"}

Timestamp: 2019-01-22 00:26:14

ServiceName:

Status: 200

RequestProtocol: HTTP/1.1

RunTime: 0

Size: 30577

UserAgent: Mozilla/5.0 (compatible; AhrefsBot/6.1; +http://ahrefs.com/robot/)

Referer: -

RemoteUser: -

RequestType: GET

RequestPath: /filter/27|13 ,27| 5 ,p53

RemoteAddr: 54.36.149.41

RefererDomain:

RequestPage: /filter/27|13 ,27| 5 ,p53

SeverityText: INFO

SeverityNumber: 9

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.027 sec.

We also extract the Body column above - in case additional attributes are added later that are not extracted by our SQL. This column should compress well in ClickHouse and will be rarely accessed, thus not impacting query performance. Finally, we reduce the Timestamp to a DateTime (to save space - see "Optimizing Types") with a cast.

Note the use of conditionals above for extracting the

SeverityTextandSeverityNumber. These are extremely useful for formulating complex conditions and checking if values are set in maps - we naively assume all keys exist in LogAttributes. We recommend users become familiar with them - they are your friend in log parsing in addition to functions for handling null values!

We require a table to receive these results. The below target table matches the above query:

CREATE TABLE otel_logs_v2

(

`Body` String,

`Timestamp` DateTime,

`ServiceName` LowCardinality(String),

`Status` UInt16,

`RequestProtocol` LowCardinality(String),

`RunTime` UInt32,

`Size` UInt32,

`UserAgent` String,

`Referer` String,

`RemoteUser` String,

`RequestType` LowCardinality(String),

`RequestPath` String,

`RemoteAddress` IPv4,

`RefererDomain` String,

`RequestPage` String,

`SeverityText` LowCardinality(String),

`SeverityNumber` UInt8

)

ENGINE = MergeTree

ORDER BY (ServiceName, Timestamp)

The types selected here are based on optimizations discussed in "Optimizing types".

Notice how we have dramatically changed our schema. In reality users will likely also have Trace columns they will want to preserve as well as the column

ResourceAttributes(this usually contains Kubernetes metadata). Grafana can exploit trace columns to provide linking functionality between logs and traces - see "Using Grafana".

Below, we create a materialized view otel_logs_mv, which executes the above select for the otel_logs table and sends the results to otel_logs_v2.

CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW otel_logs_mv TO otel_logs_v2 AS

SELECT

Body,

Timestamp::DateTime AS Timestamp,

ServiceName,

LogAttributes['status']::UInt16 AS Status,

LogAttributes['request_protocol'] AS RequestProtocol,

LogAttributes['run_time'] AS RunTime,

LogAttributes['size'] AS Size,

LogAttributes['user_agent'] AS UserAgent,

LogAttributes['referer'] AS Referer,

LogAttributes['remote_user'] AS RemoteUser,

LogAttributes['request_type'] AS RequestType,

LogAttributes['request_path'] AS RequestPath,

LogAttributes['remote_addr'] AS RemoteAddress,

domain(LogAttributes['referer']) AS RefererDomain,

path(LogAttributes['request_path']) AS RequestPage,

multiIf(Status::UInt64 > 500, 'CRITICAL', Status::UInt64 > 400, 'ERROR', Status::UInt64 > 300, 'WARNING', 'INFO') AS SeverityText,

multiIf(Status::UInt64 > 500, 20, Status::UInt64 > 400, 17, Status::UInt64 > 300, 13, 9) AS SeverityNumber

FROM otel_logs

This above is visualized below:

If we now restart the collector config used in "Exporting to ClickHouse" data will appear in otel_logs_v2 in our desired format. Note the use of typed JSON extract functions.

SELECT *

FROM otel_logs_v2

LIMIT 1

FORMAT Vertical

Row 1:

──────

Body: {"remote_addr":"54.36.149.41","remote_user":"-","run_time":"0","time_local":"2019-01-22 00:26:14.000","request_type":"GET","request_path":"\/filter\/27|13 ,27| 5 ,p53","request_protocol":"HTTP\/1.1","status":"200","size":"30577","referer":"-","user_agent":"Mozilla\/5.0 (compatible; AhrefsBot\/6.1; +http:\/\/ahrefs.com\/robot\/)"}

Timestamp: 2019-01-22 00:26:14

ServiceName:

Status: 200

RequestProtocol: HTTP/1.1

RunTime: 0

Size: 30577

UserAgent: Mozilla/5.0 (compatible; AhrefsBot/6.1; +http://ahrefs.com/robot/)

Referer: -

RemoteUser: -

RequestType: GET

RequestPath: /filter/27|13 ,27| 5 ,p53

RemoteAddress: 54.36.149.41

RefererDomain:

RequestPage: /filter/27|13 ,27| 5 ,p53

SeverityText: INFO

SeverityNumber: 9

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.010 sec.

An equivalent Materialized view, which relies on extracting columns from the Body column using JSON functions is shown below:

CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW otel_logs_mv TO otel_logs_v2 AS

SELECT Body,

Timestamp::DateTime AS Timestamp,

ServiceName,

JSONExtractUInt(Body, 'status') AS Status,

JSONExtractString(Body, 'request_protocol') AS RequestProtocol,

JSONExtractUInt(Body, 'run_time') AS RunTime,

JSONExtractUInt(Body, 'size') AS Size,

JSONExtractString(Body, 'user_agent') AS UserAgent,

JSONExtractString(Body, 'referer') AS Referer,

JSONExtractString(Body, 'remote_user') AS RemoteUser,

JSONExtractString(Body, 'request_type') AS RequestType,

JSONExtractString(Body, 'request_path') AS RequestPath,

JSONExtractString(Body, 'remote_addr') AS remote_addr,

domain(JSONExtractString(Body, 'referer')) AS RefererDomain,

path(JSONExtractString(Body, 'request_path')) AS RequestPage,

multiIf(Status::UInt64 > 500, 'CRITICAL', Status::UInt64 > 400, 'ERROR', Status::UInt64 > 300, 'WARNING', 'INFO') AS SeverityText,

multiIf(Status::UInt64 > 500, 20, Status::UInt64 > 400, 17, Status::UInt64 > 300, 13, 9) AS SeverityNumber

FROM otel_logs

Beware types

The above materialized views rely on impliciting casting - especially in the case of using the LogAttributes map. ClickHouse will often transparently cast the extracted value to the target table type, reducing the syntax required. However, we recommend users always test their views by using the views SELECT statement with an INSERT INTO statement with a target table using the same schema. This should confirm that types are correctly handled. Special attention should be given to the following cases:

- If a key doesn't exist in a map, an empty string will be returned. In the case of numerics, users will need to map these to an appropriate value. This can be achieved with conditionals e.g.

if(LogAttributes['status'] = ", 200, LogAttributes['status'])or cast functions if default values are acceptable e.g.toUInt8OrDefault(LogAttributes['status'] ) - Some types will not always be cast e.g. string representations of numerics will not be cast to enum values.

- JSON extract functions return default values for their type if a value is not found. Ensure these values make sense!

Avoid using Nullable in Clickhouse for Observability data. It is rarely required in logs and traces to be able to distinguish between empty and null. This feature incurs an additional storage overhead and will negatively impact query performance. See here for further details.

Choosing a primary (ordering) key

Once you have extracted your desired columns, you can begin optimizing your ordering/primary key.

Some simple rules can be applied to help choose an ordering key. The following can sometimes be in conflict, so consider these in order. Users can identify a number of keys from this process, with 4-5 typically sufficient:

- Select columns that align with your common filters and access patterns. If users typically start Observability investigations by filtering by a specific column e.g. pod name, this column will be used frequently in

WHEREclauses. Prioritize including these in your key over those which are used less frequently. - Prefer columns which help exclude a large percentage of the total rows when filtered, thus reducing the amount of data which needs to be read. Service names and status codes are often good candidates - in the latter case only if users filter by values which exclude most rows e.g. filtering by 200s will in most systems match most rows, in comparison to 500 errors which will correspond to a small subset.

- Prefer columns that are likely to be highly correlated with other columns in the table. This will help ensure these values are also stored contiguously, improving compression.

GROUP BYandORDER BYoperations for columns in the ordering key can be made more memory efficient.

On identifying the subset of columns for the ordering key, they must be declared in a specific order. This order can significantly influence both the efficiency of the filtering on secondary key columns in queries and the compression ratio for the table's data files. In general, it is best to order the keys in ascending order of cardinality. This should be balanced against the fact that filtering on columns that appear later in the ordering key will be less efficient than filtering on those that appear earlier in the tuple. Balance these behaviors and consider your access patterns. Most importantly, test variants. For further understanding of ordering keys and how to optimize them, we recommend this article.

We recommend deciding on your ordering keys once you have structured your logs. Do not use keys in attribute maps for the ordering key or JSON extraction expressions. Ensure you have your ordering keys as root columns in your table.

Using maps

Earlier examples show the use of map syntax map['key'] to access values in the Map(String, String) columns. As well as using map notation to access the nested keys, specialized ClickHouse map functions are available for filtering or selecting these columns.

For example, the following query identifies all of the unique keys available in the LogAttributes column using the mapKeys function followed by the groupArrayDistinctArray function (a combinator).

SELECT groupArrayDistinctArray(mapKeys(LogAttributes))

FROM otel_logs

FORMAT Vertical

Row 1:

──────

groupArrayDistinctArray(mapKeys(LogAttributes)): ['remote_user','run_time','request_type','log.file.name','referer','request_path','status','user_agent','remote_addr','time_local','size','request_protocol']

1 row in set. Elapsed: 1.139 sec. Processed 5.63 million rows, 2.53 GB (4.94 million rows/s., 2.22 GB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 71.90 MiB.

We don't recommend using dots in Map column names and may deprecate its use. Use an

_.

Using Aliases

Querying map types is slower than querying normal columns - see "Accelerating queries". In addition, it's more syntactically complicated and can be cumbersome for users to write. To address this latter issue we recommend using Alias columns.

ALIAS columns are calculated at query time and are not stored in the table. Therefore, it is impossible to INSERT a value into a column of this type. Using aliases we can reference map keys and simplify syntax, transparently expose map entries as a normal column. Consider the following example:

CREATE TABLE otel_logs

(

`Timestamp` DateTime64(9) CODEC(Delta(8), ZSTD(1)),

`TraceId` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`SpanId` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`TraceFlags` UInt32 CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`SeverityText` LowCardinality(String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`SeverityNumber` Int32 CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ServiceName` LowCardinality(String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`Body` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ResourceSchemaUrl` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ResourceAttributes` Map(LowCardinality(String), String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ScopeSchemaUrl` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ScopeName` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ScopeVersion` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ScopeAttributes` Map(LowCardinality(String), String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`LogAttributes` Map(LowCardinality(String), String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`RequestPath` String MATERIALIZED path(LogAttributes['request_path']),

`RequestType` LowCardinality(String) MATERIALIZED LogAttributes['request_type'],

`RefererDomain` String MATERIALIZED domain(LogAttributes['referer']),

`RemoteAddr` IPv4 ALIAS LogAttributes['remote_addr']

)

ENGINE = MergeTree

PARTITION BY toDate(Timestamp)

ORDER BY (ServiceName, Timestamp)

We have several materialized columns and an ALIAS column, RemoteAddr, that accesses the map LogAttributes. We can now query the LogAttributes['remote_addr']` values via this column, thus simplifying our query, i.e.

SELECT RemoteAddr

FROM default.otel_logs

LIMIT 5

┌─RemoteAddr────┐

│ 54.36.149.41 │

│ 31.56.96.51 │

│ 31.56.96.51 │

│ 40.77.167.129 │

│ 91.99.72.15 │

└───────────────┘

5 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.011 sec.

Furthermore, adding ALIAS is trivial via the ALTER TABLE command. These columns are immediately available e.g.

ALTER TABLE default.otel_logs

(ADD COLUMN `Size` String ALIAS LogAttributes['size'])

SELECT Size

FROM default.otel_logs_v3

LIMIT 5

┌─Size──┐

│ 30577 │

│ 5667 │

│ 5379 │

│ 1696 │

│ 41483 │

└───────┘

5 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.014 sec.

By default,

SELECT *excludes ALIAS columns. This behavior can be disabled by settingasterisk_include_alias_columns=1.

Optimizing types

The general Clickhouse best practices for optimizing types apply to the ClickHouse use case.

Using Codecs

In addition to type optimizations, users can follow the general best practices for codecs when attempting to optimize compression for ClickHouse Observability schemas.

In general, users will find the ZSTD codec highly applicable to logging and trace datasets. Increasing the compression value from its default 1 may improve compression. This should, however, be tested, as higher values incur a greater CPU overhead at insert time. Typically, we see little gain from increasing this value.

Furthermore, timestamps, while benefiting from delta encoding with respect to compression, have been shown to cause slow query performance if this column is used in the primary/ordering key. We recommend users assess the respective compression vs. query performance tradeoffs.

Using Dictionaries

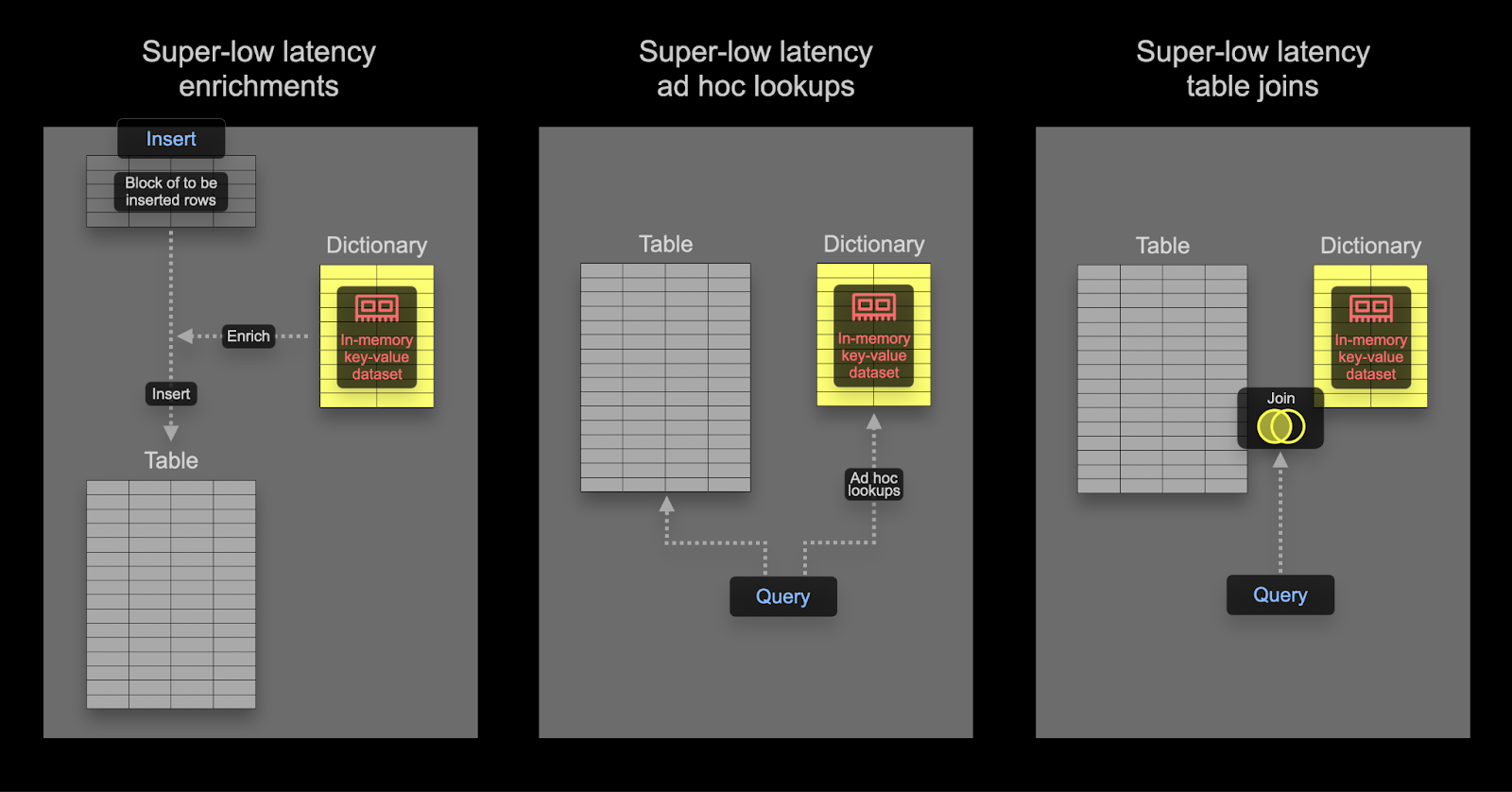

Dictionaries are a key feature of ClickHouse providing in-memory key-value representation of data from various internal and external sources, optimized for super-low latency lookup queries.

This is handy in various scenarios, from enriching ingested data on the fly without slowing down the ingestion process and improving the performance of queries in general, with JOINs particularly benefiting. While joins are rarely required in Observability use cases, dictionaries can still be handy for enrichment purposes - at both insert and query time. We provide examples of both below.

Users interested in accelerating joins with dictionaries can find further details here.

Insert time vs query time

Dictionaries can be used for enriching datasets at query time or insert time. Each of these approaches have their respective pros and cons. In summary:

- Insert time - This is typically appropriate if the enrichment value does not change and exists in an external source which can be used to populate the dictionary. In this case, enriching the row at insert time avoids the query time lookup to the dictionary. This comes at the cost of insert performance as well as an additional storage overhead, as enriched values will be stored as columns.

- Query time - If values in a dictionary change frequently, query time lookups are often more applicable. This avoids needing to update columns (and rewrite data) if mapped values change. This flexibility comes at the expense of a query time lookup cost. This query time cost is typically appreciable if a lookup is required for many rows, e.g., using a dictionary lookup in a filter clause. For result enrichment, i.e. in the

SELECT, this overhead is typically not appreciable.

We recommend that users familiarize themselves with the basics of dictionaries. Dictionaries provide an in-memory lookup table from which values can be retrieved using dedicated specialist functions.

For simple enrichment examples see the guide on Dictionaries here. Below, we focus on common observability enrichment tasks.

Using IP Dictionaries

Geo-enriching logs and traces with latitude and longitude values using IP addresses is a common Observability requirement. We can achieve this using ip_trie structured dictionary.

We use the publicly available DB-IP city-level dataset provided by DB-IP.com under the terms of the CC BY 4.0 license.

From the readme, we can see that the data is structured as follows:

| ip_range_start | ip_range_end | country_code | state1 | state2 | city | postcode | latitude | longitude | timezone |

Given this structure, let's start by taking a peek at the data using the url() table function:

SELECT *

FROM url('https://raw.githubusercontent.com/sapics/ip-location-db/master/dbip-city/dbip-city-ipv4.csv.gz', 'CSV', '\n \tip_range_start IPv4, \n \tip_range_end IPv4, \n \tcountry_code Nullable(String), \n \tstate1 Nullable(String), \n \tstate2 Nullable(String), \n \tcity Nullable(String), \n \tpostcode Nullable(String), \n \tlatitude Float64, \n \tlongitude Float64, \n \ttimezone Nullable(String)\n \t')

LIMIT 1

FORMAT Vertical

Row 1:

──────

ip_range_start: 1.0.0.0

ip_range_end: 1.0.0.255

country_code: AU

state1: Queensland

state2: ᴺᵁᴸᴸ

city: South Brisbane

postcode: ᴺᵁᴸᴸ

latitude: -27.4767

longitude: 153.017

timezone: ᴺᵁᴸᴸ

To make our lives easier, let's use the URL() table engine to create a ClickHouse table object with our field names and confirm the total number of rows:

CREATE TABLE geoip_url(

ip_range_start IPv4,

ip_range_end IPv4,

country_code Nullable(String),

state1 Nullable(String),

state2 Nullable(String),

city Nullable(String),

postcode Nullable(String),

latitude Float64,

longitude Float64,

timezone Nullable(String)

) engine=URL('https://raw.githubusercontent.com/sapics/ip-location-db/master/dbip-city/dbip-city-ipv4.csv.gz', 'CSV')

select count() from geoip_url;

┌─count()─┐

│ 3261621 │ -- 3.26 million

└─────────┘

Because our ip_trie dictionary requires IP address ranges to be expressed in CIDR notation, we’ll need to transform ip_range_start and ip_range_end.

This CDIR for each range can be succinctly computed with the following query:

with

bitXor(ip_range_start, ip_range_end) as xor,

if(xor != 0, ceil(log2(xor)), 0) as unmatched,

32 - unmatched as cidr_suffix,

toIPv4(bitAnd(bitNot(pow(2, unmatched) - 1), ip_range_start)::UInt64) as cidr_address

select

ip_range_start,

ip_range_end,

concat(toString(cidr_address),'/',toString(cidr_suffix)) as cidr

from

geoip_url

limit 4;

┌─ip_range_start─┬─ip_range_end─┬─cidr───────┐

│ 1.0.0.0 │ 1.0.0.255 │ 1.0.0.0/24 │

│ 1.0.1.0 │ 1.0.3.255 │ 1.0.0.0/22 │

│ 1.0.4.0 │ 1.0.7.255 │ 1.0.4.0/22 │

│ 1.0.8.0 │ 1.0.15.255 │ 1.0.8.0/21 │

└────────────────┴──────────────┴────────────┘

4 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.259 sec.

There is alot going on in the above query. For those interested, read this excellent explanation. Otherwise accept the above computes a CIDR for an IP range.

For our purposes, we'll only need the IP range, country code, and coordinates, so let's create a new table and insert our GeoIP data:

CREATE TABLE geoip

(

`cidr` String,

`latitude` Float64,

`longitude` Float64,

`country_code` String

)

ENGINE = MergeTree

ORDER BY cidr

INSERT INTO geoip

WITH

bitXor(ip_range_start, ip_range_end) as xor,

if(xor != 0, ceil(log2(xor)), 0) as unmatched,

32 - unmatched as cidr_suffix,

toIPv4(bitAnd(bitNot(pow(2, unmatched) - 1), ip_range_start)::UInt64) as cidr_address

SELECT

concat(toString(cidr_address),'/',toString(cidr_suffix)) as cidr,

latitude,

longitude,

country_code

FROM geoip_url

In order to perform low-latency IP lookups in ClickHouse, we'll leverage dictionaries to store key -> attributes mapping for our GeoIP data in-memory. ClickHouse provides an ip_trie dictionary structure to map our network prefixes (CIDR blocks) to coordinates and country codes. The following specifies a dictionary using this layout and the above table as the source.

CREATE DICTIONARY ip_trie (

cidr String,

latitude Float64,

longitude Float64,

country_code String

)

primary key cidr

source(clickhouse(table 'geoip'))

layout(ip_trie)

lifetime(3600);

We can select rows from the dictionary and confirm this dataset is available for lookups:

SELECT * FROM ip_trie LIMIT 3

┌─cidr───────┬─latitude─┬─longitude─┬─country_code─┐

│ 1.0.0.0/22 │ 26.0998 │ 119.297 │ CN │

│ 1.0.0.0/24 │ -27.4767 │ 153.017 │ AU │

│ 1.0.4.0/22 │ -38.0267 │ 145.301 │ AU │

└────────────┴──────────┴───────────┴──────────────┘

3 rows in set. Elapsed: 4.662 sec.

Dictionaries in ClickHouse are periodically refreshed based on the underlying table data and the lifetime clause used above. To update our GeoIP dictionary to reflect the latest changes in the DB-IP dataset, we'll just need to reinsert data from the geoip_url remote table to our

geoiptable with transformations applied.

Now that we have GeoIP data loaded into our ip_trie dictionary (conveniently also named ip_trie), we can use it for IP geolocation. This can be accomplished using the dictGet() function as follows:

SELECT dictGet('ip_trie', ('country_code', 'latitude', 'longitude'), CAST('85.242.48.167', 'IPv4')) AS ip_details

┌─ip_details──────────────┐

│ ('PT',38.7944,-9.34284) │

└─────────────────────────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.003 sec.

Notice the retrieval speed here. This allows us to enrich logs. In this case, we choose to perform query time enrichment.

Returning to our original logs dataset, we can use the above to aggregate our logs by country. The following assumes we use the schema resulting from our earlier materialized view, which has an extracted RemoteAddress column.

SELECT dictGet('ip_trie', 'country_code', tuple(RemoteAddress)) AS country,

formatReadableQuantity(count()) AS num_requests

FROM default.otel_logs_v2

WHERE country != ''

GROUP BY country

ORDER BY count() DESC

LIMIT 5

┌─country─┬─num_requests────┐

│ IR │ 7.36 million │

│ US │ 1.67 million │

│ AE │ 526.74 thousand │

│ DE │ 159.35 thousand │

│ FR │ 109.82 thousand │

└─────────┴─────────────────┘

5 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.140 sec. Processed 20.73 million rows, 82.92 MB (147.79 million rows/s., 591.16 MB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 1.16 MiB.

Since an IP to geographical location mapping may change, users are likely to want to know from where the request originated at the time it was made - not what the current geographic location for the same address is. For this reason, index time enrichment is likely preferred here. This can be done using materialized columns as shown below or in the select of a materialized view:

CREATE TABLE otel_logs_v2

(

`Body` String,

`Timestamp` DateTime,

`ServiceName` LowCardinality(String),

`Status` UInt16,

`RequestProtocol` LowCardinality(String),

`RunTime` UInt32,

`Size` UInt32,

`UserAgent` String,

`Referer` String,

`RemoteUser` String,

`RequestType` LowCardinality(String),

`RequestPath` String,

`RemoteAddress` IPv4,

`RefererDomain` String,

`RequestPage` String,

`SeverityText` LowCardinality(String),

`SeverityNumber` UInt8,

`Country` String MATERIALIZED dictGet('ip_trie', 'country_code', tuple(RemoteAddress)),

`Latitude` Float32 MATERIALIZED dictGet('ip_trie', 'latitude', tuple(RemoteAddress)),

`Longitude` Float32 MATERIALIZED dictGet('ip_trie', 'longitude', tuple(RemoteAddress))

)

ENGINE = MergeTree

ORDER BY (ServiceName, Timestamp)

Users are likely to want the ip enrichment dictionary to be periodically updated based on new data. This can be achieved using the

LIFETIMEclause of the dictionary which will cause the dictionary to be periodically reloaded from the underlying table. To update the underlying table, see "Using refreshable Materialized views".

The above countries and coordinates offer visualization capabilities beyond grouping and filtering by country. For inspiration see "Visualizing geo data".

Using Regex Dictionaries (User Agent parsing)

The parsing of user agent strings is a classical regular expression problem and a common requirement in log and trace based datasets. ClickHouse provides efficient parsing of user agents using Regular Expression Tree Dictionaries.

Regular expression tree dictionaries are defined in ClickHouse open-source using the YAMLRegExpTree dictionary source type which provides the path to a YAML file containing the regular expression tree. Should you wish to provide your own regular expression dictionary, the details on the required structure can be found here. Below we focus on user-agent parsing using uap-core and load our dictionary for the supported CSV format. This approach is compatible with OSS and ClickHouse Cloud.

In the examples below, we use snapshots of the latest uap-core regular expressions for user-agent parsing from June 2024. The latest file, which is occasionally updated, can be found here. Users can follow the steps here to load into the CSV file used below.

Create the following Memory tables. These hold our regular expressions for parsing devices, browsers and operating systems.

CREATE TABLE regexp_os

(

id UInt64,

parent_id UInt64,

regexp String,

keys Array(String),

values Array(String)

) ENGINE=Memory;

CREATE TABLE regexp_browser

(

id UInt64,

parent_id UInt64,

regexp String,

keys Array(String),

values Array(String)

) ENGINE=Memory;

CREATE TABLE regexp_device

(

id UInt64,

parent_id UInt64,

regexp String,

keys Array(String),

values Array(String)

) ENGINE=Memory;

These tables can be populated from the following publicly hosted CSV files, using the url table function:

INSERT INTO regexp_os SELECT * FROM s3('https://datasets-documentation.s3.eu-west-3.amazonaws.com/user_agent_regex/regexp_os.csv', 'CSV', 'id UInt64, parent_id UInt64, regexp String, keys Array(String), values Array(String)')

INSERT INTO regexp_device SELECT * FROM s3('https://datasets-documentation.s3.eu-west-3.amazonaws.com/user_agent_regex/regexp_device.csv', 'CSV', 'id UInt64, parent_id UInt64, regexp String, keys Array(String), values Array(String)')

INSERT INTO regexp_browser SELECT * FROM s3('https://datasets-documentation.s3.eu-west-3.amazonaws.com/user_agent_regex/regexp_browser.csv', 'CSV', 'id UInt64, parent_id UInt64, regexp String, keys Array(String), values Array(String)')

With our memory tables populated, we can load our Regular Expression dictionaries. Note that we need to specify the key values as columns - these will be the attributes we can extract from the user agent.

CREATE DICTIONARY regexp_os_dict

(

regexp String,

os_replacement String default 'Other',

os_v1_replacement String default '0',

os_v2_replacement String default '0',

os_v3_replacement String default '0',

os_v4_replacement String default '0'

)

PRIMARY KEY regexp

SOURCE(CLICKHOUSE(TABLE 'regexp_os'))

LIFETIME(MIN 0 MAX 0)

LAYOUT(REGEXP_TREE);

CREATE DICTIONARY regexp_device_dict

(

regexp String,

device_replacement String default 'Other',

brand_replacement String,

model_replacement String

)

PRIMARY KEY(regexp)

SOURCE(CLICKHOUSE(TABLE 'regexp_device'))

LIFETIME(0)

LAYOUT(regexp_tree);

CREATE DICTIONARY regexp_browser_dict

(

regexp String,

family_replacement String default 'Other',

v1_replacement String default '0',

v2_replacement String default '0'

)

PRIMARY KEY(regexp)

SOURCE(CLICKHOUSE(TABLE 'regexp_browser'))

LIFETIME(0)

LAYOUT(regexp_tree);

With these dictionaries loaded we can provide a sample user-agent and test our new dictionary extraction capabilities:

WITH 'Mozilla/5.0 (Macintosh; Intel Mac OS X 10.15; rv:127.0) Gecko/20100101 Firefox/127.0' AS user_agent

SELECT

dictGet('regexp_device_dict', ('device_replacement', 'brand_replacement', 'model_replacement'), user_agent) AS device,

dictGet('regexp_browser_dict', ('family_replacement', 'v1_replacement', 'v2_replacement'), user_agent) AS browser,

dictGet('regexp_os_dict', ('os_replacement', 'os_v1_replacement', 'os_v2_replacement', 'os_v3_replacement'), user_agent) AS os

┌─device────────────────┬─browser───────────────┬─os─────────────────────────┐

│ ('Mac','Apple','Mac') │ ('Firefox','127','0') │ ('Mac OS X','10','15','0') │

└───────────────────────┴───────────────────────┴────────────────────────────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.003 sec.

Given the rules surrounding user agents will rarely change, with the dictionary only needing updating in response to new browsers, operating systems, and devices, it makes sense to perform this extraction at insert time.

We can either perform this work using a materialized column or using a materialized view. Below we modify the materialized view used earlier:

CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW otel_logs_mv TO otel_logs_v2

AS SELECT

Body,

CAST(Timestamp, 'DateTime') AS Timestamp,

ServiceName,

LogAttributes['status'] AS Status,

LogAttributes['request_protocol'] AS RequestProtocol,

LogAttributes['run_time'] AS RunTime,

LogAttributes['size'] AS Size,

LogAttributes['user_agent'] AS UserAgent,

LogAttributes['referer'] AS Referer,

LogAttributes['remote_user'] AS RemoteUser,

LogAttributes['request_type'] AS RequestType,

LogAttributes['request_path'] AS RequestPath,

LogAttributes['remote_addr'] AS RemoteAddress,

domain(LogAttributes['referer']) AS RefererDomain,

path(LogAttributes['request_path']) AS RequestPage,

multiIf(CAST(Status, 'UInt64') > 500, 'CRITICAL', CAST(Status, 'UInt64') > 400, 'ERROR', CAST(Status, 'UInt64') > 300, 'WARNING', 'INFO') AS SeverityText,

multiIf(CAST(Status, 'UInt64') > 500, 20, CAST(Status, 'UInt64') > 400, 17, CAST(Status, 'UInt64') > 300, 13, 9) AS SeverityNumber,

dictGet('regexp_device_dict', ('device_replacement', 'brand_replacement', 'model_replacement'), UserAgent) AS Device,

dictGet('regexp_browser_dict', ('family_replacement', 'v1_replacement', 'v2_replacement'), UserAgent) AS Browser,

dictGet('regexp_os_dict', ('os_replacement', 'os_v1_replacement', 'os_v2_replacement', 'os_v3_replacement'), UserAgent) AS Os

FROM otel_logs

This requires us modify the schema for the target table otel_logs_v2:

CREATE TABLE default.otel_logs_v2

(

`Body` String,

`Timestamp` DateTime,

`ServiceName` LowCardinality(String),

`Status` UInt8,

`RequestProtocol` LowCardinality(String),

`RunTime` UInt32,

`Size` UInt32,

`UserAgent` String,

`Referer` String,

`RemoteUser` String,

`RequestType` LowCardinality(String),

`RequestPath` String,

`remote_addr` IPv4,

`RefererDomain` String,

`RequestPage` String,

`SeverityText` LowCardinality(String),

`SeverityNumber` UInt8,

`Device` Tuple(device_replacement LowCardinality(String), brand_replacement LowCardinality(String), model_replacement LowCardinality(String)),

`Browser` Tuple(family_replacement LowCardinality(String), v1_replacement LowCardinality(String), v2_replacement LowCardinality(String)),

`Os` Tuple(os_replacement LowCardinality(String), os_v1_replacement LowCardinality(String), os_v2_replacement LowCardinality(String), os_v3_replacement LowCardinality(String))

)

ENGINE = MergeTree

ORDER BY (ServiceName, Timestamp, Status)

After restarting the collector and ingesting structured logs, based on earlier documented steps, we can query our newly extracted Device, Browser and Os columns.

SELECT Device, Browser, Os

FROM otel_logs_v2

LIMIT 1

FORMAT Vertical

Row 1:

──────

Device: ('Spider','Spider','Desktop')

Browser: ('AhrefsBot','6','1')

Os: ('Other','0','0','0')

Note the use of Tuples for these user agent columns. Tuples are recommended for complex structures where the hierarchy is known in advance. Sub-columns offer the same performance as regular columns (unlike Map keys) while allowing heterogeneous types.

Further reading

For more examples and details on dictionaries, we recommend the following articles:

Accelerating queries

ClickHouse supports a number of techniques for accelerating query performance. The following should be considered only after choosing an appropriate primary/ordering key to optimize for the most popular access patterns and to maximize compression. This will usually have the largest impact on performance for the least effort.

Using Materialized views (incremental) for aggregations

In earlier sections, we explored the use of Materialized views for data transformation and filtering. Materialized views can, however, also be used to precompute aggregations at insert time and store the result. This result can be updated with the results from subsequent inserts, thus effectively allowing an aggregation to be precomputed at insert time.

The principal idea here is that the results will often be a smaller representation of the original data (a partial sketch in the case of aggregations). When combined with a simpler query for reading the results from the target table, query times will be faster than if the same computation was performed on the original data.

Consider the following query, where we compute the total traffic per hour using our structured logs:

SELECT toStartOfHour(Timestamp) AS Hour,

sum(toUInt64OrDefault(LogAttributes['size'])) AS TotalBytes

FROM otel_logs

GROUP BY Hour

ORDER BY Hour DESC

LIMIT 5

┌────────────────Hour─┬─TotalBytes─┐

│ 2019-01-26 16:00:00 │ 1661716343 │

│ 2019-01-26 15:00:00 │ 1824015281 │

│ 2019-01-26 14:00:00 │ 1506284139 │

│ 2019-01-26 13:00:00 │ 1580955392 │

│ 2019-01-26 12:00:00 │ 1736840933 │

└─────────────────────┴────────────┘

5 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.666 sec. Processed 10.37 million rows, 4.73 GB (15.56 million rows/s., 7.10 GB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 1.40 MiB.

We can imagine this might be a common line chart users plot with Grafana. This query is admittedly very fast - the dataset is only 10m rows, and ClickHouse is fast! However, if we scale this to billions and trillions of rows, we would ideally like to sustain this query performance.

This query would be 10x faster if we used the

otel_logs_v2table, which results from our earlier materialized view, which extracts the size key from theLogAttributesmap. We use the raw data here for illustrative purposes only and would recommend using the earlier view if this is a common query.

We need a table to receive the results if we want to compute this at insert time using a Materialized view. This table should only keep 1 row per hour. If an update is received for an existing hour, the other columns should be merged into the existing hour’s row. For this merge of incremental states to happen, partial states must be stored for the other columns.

This requires a special engine type in ClickHouse: The SummingMergeTree. This replaces all the rows with the same ordering key with one row which contains summed values for the numeric columns. The following table will merge any rows with the same date, summing any numerical columns.

CREATE TABLE bytes_per_hour

(

`Hour` DateTime,

`TotalBytes` UInt64

)

ENGINE = SummingMergeTree

ORDER BY Hour

To demonstrate our materialized view, assume our bytes_per_hour table is empty and yet to receive any data. Our materialized view performs the above SELECT on data inserted into otel_logs (this will be performed over blocks of a configured size), with the results sent to bytes_per_hour. The syntax is shown below:

CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW bytes_per_hour_mv TO bytes_per_hour AS

SELECT toStartOfHour(Timestamp) AS Hour,

sum(toUInt64OrDefault(LogAttributes['size'])) AS TotalBytes

FROM otel_logs

GROUP BY Hour

The TO clause here is key, denoting where results will be sent to i.e. bytes_per_hour.

If we restart our Otel Collector and resend the logs, the bytes_per_hour table will be incrementally populated with the above query result. On completion, we can confirm the size of our bytes_per_hour - we should have 1 row per hour:

SELECT count()

FROM bytes_per_hour

FINAL

┌─count()─┐

│ 113 │

└─────────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.039 sec.

We've effectively reduced the number of rows here from 10m (in otel_logs) to 113 by storing the result of our query. The key here is that if new logs are inserted into the otel_logs table, new values will be sent to bytes_per_hour for their respective hour, where they will be automatically merged asynchronously in the background - by keeping only one row per hour bytes_per_hour will thus always be both small and up-to-date.

Since the merging of rows is asynchronous, there may be more than one row per hour when a user queries. To ensure any outstanding rows are merged at query time, we have two options:

Use the FINAL modifier on the table name. We did this for the count query above.

Aggregate by the ordering key used in our final table i.e. Timestamp and sum the metrics. Typically, this is more efficient and flexible (the table can be used for other things), but the former can be simpler for some queries. We show both below:

SELECT

Hour,

sum(TotalBytes) AS TotalBytes

FROM bytes_per_hour

GROUP BY Hour

ORDER BY Hour DESC

LIMIT 5

┌────────────────Hour─┬─TotalBytes─┐

│ 2019-01-26 16:00:00 │ 1661716343 │

│ 2019-01-26 15:00:00 │ 1824015281 │

│ 2019-01-26 14:00:00 │ 1506284139 │

│ 2019-01-26 13:00:00 │ 1580955392 │

│ 2019-01-26 12:00:00 │ 1736840933 │

└─────────────────────┴────────────┘

5 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.008 sec.

SELECT

Hour,

TotalBytes

FROM bytes_per_hour

FINAL

ORDER BY Hour DESC

LIMIT 5

┌────────────────Hour─┬─TotalBytes─┐

│ 2019-01-26 16:00:00 │ 1661716343 │

│ 2019-01-26 15:00:00 │ 1824015281 │

│ 2019-01-26 14:00:00 │ 1506284139 │

│ 2019-01-26 13:00:00 │ 1580955392 │

│ 2019-01-26 12:00:00 │ 1736840933 │

└─────────────────────┴────────────┘

5 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.005 sec.

This has sped up our query from 0.6s to 0.008s over 75 times!

These savings can be even greater on larger datasets with more complex queries. See here for examples.

A more complex example

The above example aggregates a simple count per hour using the SummingMergeTree. Statistics beyond simple sums require a different target table engine: the AggregatingMergeTree.

Suppose we wish to compute the number of unique IP addresses (or unique users) per day. The query for this:

SELECT toStartOfHour(Timestamp) AS Hour, uniq(LogAttributes['remote_addr']) AS UniqueUsers

FROM otel_logs

GROUP BY Hour

ORDER BY Hour DESC

┌────────────────Hour─┬─UniqueUsers─┐

│ 2019-01-26 16:00:00 │ 4763 │

…

│ 2019-01-22 00:00:00 │ 536 │

└─────────────────────┴────────────┘

113 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.667 sec. Processed 10.37 million rows, 4.73 GB (15.53 million rows/s., 7.09 GB/s.)

In order to persist a cardinality count for incremental update the AggregatingMergeTree is required.

CREATE TABLE unique_visitors_per_hour

(

`Hour` DateTime,

`UniqueUsers` AggregateFunction(uniq, IPv4)

)

ENGINE = AggregatingMergeTree

ORDER BY Hour

To ensure ClickHouse knows that aggregate states will be stored, we define the UniqueUsers column as the type AggregateFunction, specifying the function source of the partial states (uniq) and the type of the source column (IPv4). Like the SummingMergeTree, rows with the same ORDER BY key value will be merged (Hour in the above example).

The associated materialized view uses the earlier query:

CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW unique_visitors_per_hour_mv TO unique_visitors_per_hour AS

SELECT toStartOfHour(Timestamp) AS Hour,

uniqState(LogAttributes['remote_addr']::IPv4) AS UniqueUsers

FROM otel_logs

GROUP BY Hour

ORDER BY Hour DESC

Note how we append the suffix State to the end of our aggregate functions. This ensures the aggregate state of the function is returned instead of the final result. This will contain additional information to allow this partial state to merge with other states.

Once the data has been reloaded, through a Collector restart, we can confirm 113 rows are available in the unique_visitors_per_hour table.

SELECT count()

FROM unique_visitors_per_hour

FINAL

┌─count()─┐

│ 113 │

└─────────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.009 sec.

Our final query needs to utilize the Merge suffix for our functions (as the columns store partial aggregation states):

SELECT Hour, uniqMerge(UniqueUsers) AS UniqueUsers

FROM unique_visitors_per_hour

GROUP BY Hour

ORDER BY Hour DESC

┌────────────────Hour─┬─UniqueUsers─┐

│ 2019-01-26 16:00:00 │ 4763 │

│ 2019-01-22 00:00:00 │ 536 │

└─────────────────────┴─────────────┘

113 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.027 sec.

Note we use a GROUP BY here instead of using FINAL.

Using Materialized views (incremental) for fast lookups

Users should consider their access patterns when choosing the ClickHouse ordering key with the columns that are frequently used in filter and aggregation clauses. This can be restrictive in Observability use cases, where users have more diverse access patterns that cannot be encapsulated in a single set of columns. This is best illustrated in an example built into the default OTel schemas. Consider the default schema for the traces:

CREATE TABLE otel_traces

(

`Timestamp` DateTime64(9) CODEC(Delta(8), ZSTD(1)),

`TraceId` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`SpanId` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ParentSpanId` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`TraceState` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`SpanName` LowCardinality(String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`SpanKind` LowCardinality(String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ServiceName` LowCardinality(String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ResourceAttributes` Map(LowCardinality(String), String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ScopeName` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`ScopeVersion` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`SpanAttributes` Map(LowCardinality(String), String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`Duration` Int64 CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`StatusCode` LowCardinality(String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`StatusMessage` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`Events.Timestamp` Array(DateTime64(9)) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`Events.Name` Array(LowCardinality(String)) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`Events.Attributes` Array(Map(LowCardinality(String), String)) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`Links.TraceId` Array(String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`Links.SpanId` Array(String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`Links.TraceState` Array(String) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`Links.Attributes` Array(Map(LowCardinality(String), String)) CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

INDEX idx_trace_id TraceId TYPE bloom_filter(0.001) GRANULARITY 1,

INDEX idx_res_attr_key mapKeys(ResourceAttributes) TYPE bloom_filter(0.01) GRANULARITY 1,

INDEX idx_res_attr_value mapValues(ResourceAttributes) TYPE bloom_filter(0.01) GRANULARITY 1,

INDEX idx_span_attr_key mapKeys(SpanAttributes) TYPE bloom_filter(0.01) GRANULARITY 1,

INDEX idx_span_attr_value mapValues(SpanAttributes) TYPE bloom_filter(0.01) GRANULARITY 1,

INDEX idx_duration Duration TYPE minmax GRANULARITY 1

)

ENGINE = MergeTree

PARTITION BY toDate(Timestamp)

ORDER BY (ServiceName, SpanName, toUnixTimestamp(Timestamp), TraceId)

This schema is optimized for filtering by ServiceName, SpanName, and Timestamp. In tracing, users also need the ability to perform lookups by a specific TraceId and retrieving the associated trace's spans. While this is present in the ordering key, its position at the end means filtering will not be as efficient and likely means significant amounts of data will need to be scanned when retrieving a single trace.

The OTel collector also installs a materialized view and associated table to address this challenge. The table and view are shown below:

CREATE TABLE otel_traces_trace_id_ts

(

`TraceId` String CODEC(ZSTD(1)),

`Start` DateTime64(9) CODEC(Delta(8), ZSTD(1)),

`End` DateTime64(9) CODEC(Delta(8), ZSTD(1)),

INDEX idx_trace_id TraceId TYPE bloom_filter(0.01) GRANULARITY 1

)

ENGINE = MergeTree

ORDER BY (TraceId, toUnixTimestamp(Start))

CREATE MATERIALIZED VIEW otel_traces_trace_id_ts_mv TO otel_traces_trace_id_ts

(

`TraceId` String,

`Start` DateTime64(9),

`End` DateTime64(9)

)

AS SELECT

TraceId,

min(Timestamp) AS Start,

max(Timestamp) AS End

FROM otel_traces

WHERE TraceId != ''

GROUP BY TraceId

The view effectively ensures the table otel_traces_trace_id_ts has the minimum and maximum Timestamp for the trace. This table, ordered by TraceId, allows these timestamps to be retrieved efficiently. These timestamp ranges can, in turn, be used when querying the main otel_traces table. More specifically, when retrieving a trace by its id, Grafana uses the following query:

WITH 'ae9226c78d1d360601e6383928e4d22d' AS trace_id,

(

SELECT min(Start)

FROM default.otel_traces_trace_id_ts

WHERE TraceId = trace_id

) AS trace_start,

(

SELECT max(End) + 1

FROM default.otel_traces_trace_id_ts

WHERE TraceId = trace_id

) AS trace_end

SELECT

TraceId AS traceID,

SpanId AS spanID,

ParentSpanId AS parentSpanID,

ServiceName AS serviceName,

SpanName AS operationName,

Timestamp AS startTime,

Duration * 0.000001 AS duration,

arrayMap(key -> map('key', key, 'value', SpanAttributes[key]), mapKeys(SpanAttributes)) AS tags,

arrayMap(key -> map('key', key, 'value', ResourceAttributes[key]), mapKeys(ResourceAttributes)) AS serviceTags

FROM otel_traces

WHERE (traceID = trace_id) AND (startTime >= trace_start) AND (startTime <= trace_end)

LIMIT 1000

The CTE here identifies the minimum and maximum timestamp for the trace id ae9226c78d1d360601e6383928e4d22d, before using this to filter the main otel_traces for its associated spans.

This same approach can be applied for similar access patterns. We explore a similar example in Data Modeling here.

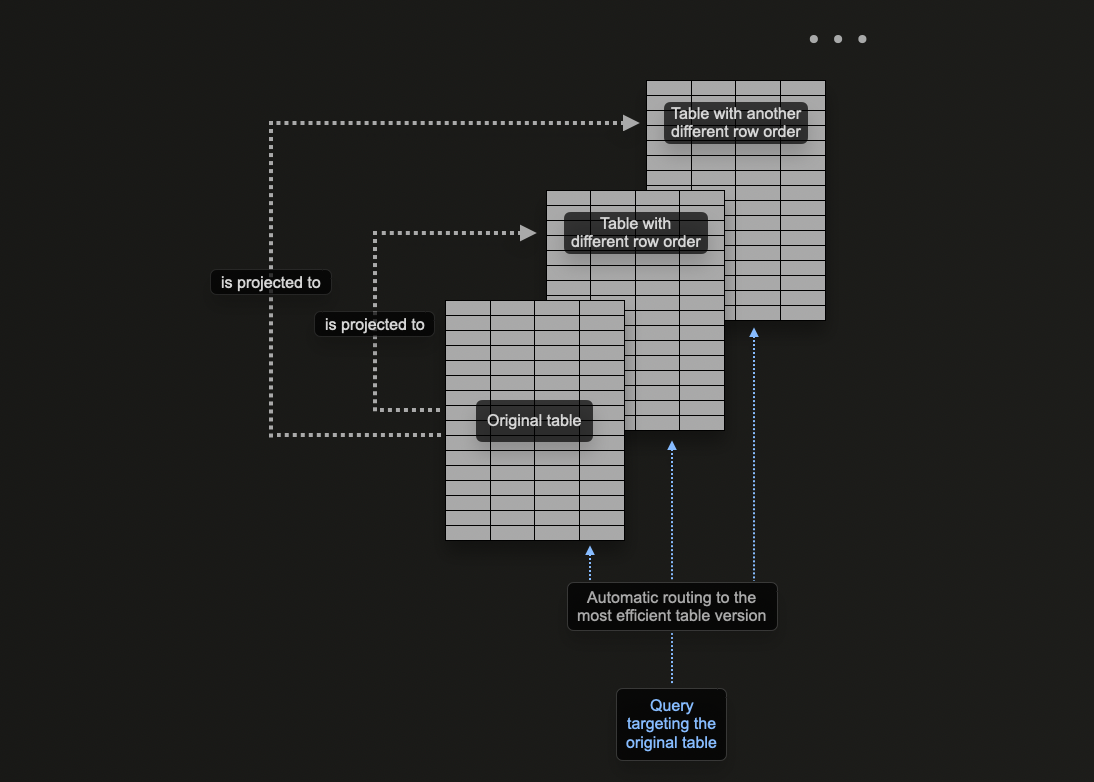

Using Projections

ClickHouse projections allow users to specify multiple ORDER BY clauses for a table.

In previous sections, we explore how materialized views can be used in ClickHouse to pre compute aggregations, transform rows and optimize Observability queries for different access patterns.

We provided an example where the materialized view sends rows to a target table with a different ordering key than the original table receiving inserts in order to optimize for lookups by trace id.

Projections can be used to address the same problem, allowing the user to optimize for queries on a column that are not part of the primary key.

In theory, this capability can be used to provide multiple ordering keys for a table, with one distinct disadvantage: data duplication. Specifically, data will need to be written in the order of the main primary key in addition to the order specified for each projection. This will slow inserts and consume more disk space.

Projections offer many of the same capabilities as materialized views, but should be used sparingly with the latter often preferred. Users should understand the drawbacks and when they appropriate. For example, while projections can be used for pre-computing aggregations we recommend users use Materialized views for this.

Consider the following query, which filters our otel_logs_v2 table by 500 error codes. This is likely a common access pattern for logging with users wanting to filter by error codes:

SELECT Timestamp, RequestPath, Status, RemoteAddress, UserAgent

FROM otel_logs_v2

WHERE Status = 500

FORMAT `Null`

Ok.

0 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.177 sec. Processed 10.37 million rows, 685.32 MB (58.66 million rows/s., 3.88 GB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 56.54 MiB.

We don't print results here using

FORMAT Null. This forces all results to be read but not returned, thus preventing an early termination of the query due to a LIMIT. This is just to show the time taken to scan all 10m rows.

The above query requires a linear scan with our chosen ordering key (ServiceName, Timestamp). While we could add Status to the end of the ordering key, improving performance for the above query, we can also add a projection.

ALTER TABLE otel_logs_v2 (

ADD PROJECTION status

(

SELECT Timestamp, RequestPath, Status, RemoteAddress, UserAgent ORDER BY Status

)

)

ALTER TABLE otel_logs_v2 MATERIALIZE PROJECTION status

Note we have to first create the projection and then materialize it. This latter command causes the data to be stored twice on disk in two different orders. The projection can also be defined when the data is created, as shown below, and will be automatically maintained as data inserted.

CREATE TABLE otel_logs_v2

(

`Body` String,

`Timestamp` DateTime,

`ServiceName` LowCardinality(String),

`Status` UInt16,

`RequestProtocol` LowCardinality(String),

`RunTime` UInt32,

`Size` UInt32,

`UserAgent` String,

`Referer` String,

`RemoteUser` String,

`RequestType` LowCardinality(String),

`RequestPath` String,

`RemoteAddress` IPv4,

`RefererDomain` String,

`RequestPage` String,

`SeverityText` LowCardinality(String),

`SeverityNumber` UInt8,

PROJECTION status

(

SELECT Timestamp, RequestPath, Status, RemoteAddress, UserAgent

ORDER BY Status

)

)

ENGINE = MergeTree

ORDER BY (ServiceName, Timestamp)

Importantly, if the projection is created via an ALTER, its creation is asynchronous when the MATERIALIZE PROJECTION command is issued. Users can confirm the progress of this operation with the following query, waiting for is_done=1.

SELECT parts_to_do, is_done, latest_fail_reason

FROM system.mutations

WHERE (`table` = 'otel_logs_v2') AND (command LIKE '%MATERIALIZE%')

┌─parts_to_do─┬─is_done─┬─latest_fail_reason─┐

│ 0 │ 1 │ │

└─────────────┴─────────┴────────────────────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.008 sec.

If we repeat the above query, we can see performance has improved significantly at the expense of additional storage (see "Measuring table size & compression" for how to measure this).

SELECT Timestamp, RequestPath, Status, RemoteAddress, UserAgent

FROM otel_logs_v2

WHERE Status = 500

FORMAT `Null`

0 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.031 sec. Processed 51.42 thousand rows, 22.85 MB (1.65 million rows/s., 734.63 MB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 27.85 MiB.

In the above example, we specify the columns used in the earlier query in the projection. This will mean only these specified columns will be stored on disk as part of the projection, ordered by Status. If alternatively, we used SELECT * here, all columns would be stored. While this would allow more queries (using any subset of columns) to benefit from the projection, additional storage will be incurred. For measuring disk space and compression, see "Measuring table size & compression".

Secondary/Data Skipping indices

No matter how well the primary key is tuned in ClickHouse, some queries will inevitably require full table scans. While this can be mitigated using Materialized views (and projections for some queries), these require additional maintenance and users to be aware of their availability in order to ensure they are exploited. While traditional relational databases solve this with secondary indexes, these are ineffective in column-oriented databases like ClickHouse. Instead, ClickHouse uses "Skip" indexes, which can significantly improve query performance by allowing the database to skip over large data chunks with no matching values.

The default OTel schemas use secondary indices in an attempt to accelerate access to map access. While we find these to be generally ineffective and do not recommend copying them into your custom schema, skipping indices can still be useful.

Users should read and understand the guide to secondary indices before attempting to apply them.

In general, they are effective when a strong correlation exists between the primary key and the targeted, non-primary column/expression and users are looking up rare values i.e. those which do not occur in many granules.

Bloom filters for text search

For Observability queries, secondary indices can be useful when users need to perform text searches. Specifically, the ngram and token-based bloom filter indexes ngrambf_v1 and tokenbf_v1 can be used to accelerate searches over String columns with the operators LIKE, IN, and hasToken. Importantly, the token-based index generates tokens using non-alphanumeric characters as a separator. This means only tokens (or whole words) can be matched at query time. For more granular matching, the N-gram bloom filter can be used. This splits strings into ngrams of a specified size, thus allowing sub-word matching.

To evaluate the tokens that will be produced and therefore, matched, the tokens function can be used:

SELECT tokens('https://www.zanbil.ir/m/filter/b113')

┌─tokens────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ ['https','www','zanbil','ir','m','filter','b113'] │

└───────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.008 sec.

The ngram function provides similar capabilities, where an ngram size can be specified as the second parameter:

SELECT ngrams('https://www.zanbil.ir/m/filter/b113', 3)

┌─ngrams('https://www.zanbil.ir/m/filter/b113', 3)────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ ['htt','ttp','tps','ps:','s:/','://','//w','/ww','www','ww.','w.z','.za','zan','anb','nbi','bil','il.','l.i','.ir','ir/','r/m','/m/','m/f','/fi','fil','ilt','lte','ter','er/','r/b','/b1','b11','113'] │

└─────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.008 sec.

ClickHouse also has experimental support for inverted indices as a secondary index. We do not currently recommend these for logging datasets but anticipate they will replace token-based bloom filters when they are production-ready.

For the purposes of example we use the structured logs dataset. Suppose we wish to count logs where the Referer column contains ultra.

SELECT count()

FROM otel_logs_v2

WHERE Referer LIKE '%ultra%'

┌─count()─┐

│ 114514 │

└─────────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.177 sec. Processed 10.37 million rows, 908.49 MB (58.57 million rows/s., 5.13 GB/s.)

Here we need to match on an ngram size of 3. We therefore create an ngrambf_v1 index.

CREATE TABLE otel_logs_bloom

(

`Body` String,

`Timestamp` DateTime,

`ServiceName` LowCardinality(String),

`Status` UInt16,

`RequestProtocol` LowCardinality(String),

`RunTime` UInt32,

`Size` UInt32,

`UserAgent` String,

`Referer` String,

`RemoteUser` String,

`RequestType` LowCardinality(String),

`RequestPath` String,

`RemoteAddress` IPv4,

`RefererDomain` String,

`RequestPage` String,

`SeverityText` LowCardinality(String),

`SeverityNumber` UInt8,

INDEX idx_span_attr_value Referer TYPE ngrambf_v1(3, 10000, 3, 7) GRANULARITY 1

)

ENGINE = MergeTree

ORDER BY (Timestamp)

The index ngrambf_v1(3, 10000, 3, 7) here takes four parameters. The last of these (value 7) represents a seed. The others represent the ngram size (3), the value m (filter size), and the number of hash functions k (7). k and m require tuning and will be based on the number of unique ngrams/tokens and the probability the filter results in a true negative - thus confirming a value is not present in a granule. We recommend these functions to help establish these values.

If tuned correctly, the speedup here can be significant:

SELECT count()

FROM otel_logs_bloom

WHERE Referer LIKE '%ultra%'

┌─count()─┐

│ 182 │

└─────────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.077 sec. Processed 4.22 million rows, 375.29 MB (54.81 million rows/s., 4.87 GB/s.)

Peak memory usage: 129.60 KiB.

The above is for illustrative purposes only. We recommend users extract structure from their logs at insert rather than attempting to optimize text searches using token-based bloom filters. There are, however, cases where users have stack traces or other large Strings for which text search can be useful due to a less deterministic structure.

Some general guidelines around using bloom filters:

The objective of the bloom is to filter granules, thus avoiding the need to load all values for a column and perform a linear scan. The EXPLAIN clause, with the parameter indexes=1, can be used to identify the number of granules that have been skipped. Consider the responses below for the original table otel_logs_v2 and the table otel_logs_bloom with an ngram bloom filter.

EXPLAIN indexes = 1

SELECT count()

FROM otel_logs_v2

WHERE Referer LIKE '%ultra%'

┌─explain────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Expression ((Project names + Projection)) │

│ Aggregating │

│ Expression (Before GROUP BY) │

│ Filter ((WHERE + Change column names to column identifiers)) │

│ ReadFromMergeTree (default.otel_logs_v2) │

│ Indexes: │

│ PrimaryKey │

│ Condition: true │

│ Parts: 9/9 │

│ Granules: 1278/1278 │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

10 rows in set. Elapsed: 0.016 sec.

EXPLAIN indexes = 1

SELECT count()

FROM otel_logs_bloom

WHERE Referer LIKE '%ultra%'

┌─explain────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┐

│ Expression ((Project names + Projection)) │

│ Aggregating │

│ Expression (Before GROUP BY) │

│ Filter ((WHERE + Change column names to column identifiers)) │

│ ReadFromMergeTree (default.otel_logs_bloom) │

│ Indexes: │

│ PrimaryKey │

│ Condition: true │

│ Parts: 8/8 │

│ Granules: 1276/1276 │

│ Skip │

│ Name: idx_span_attr_value │

│ Description: ngrambf_v1 GRANULARITY 1 │

│ Parts: 8/8 │

│ Granules: 517/1276 │

└────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────────┘

The bloom filter will typically only be faster if it's smaller than the column itself. If it's larger, then there is likely to be negligible performance benefit. Compare the size of the filter to the column using the following queries:

SELECT

name,

formatReadableSize(sum(data_compressed_bytes)) AS compressed_size,

formatReadableSize(sum(data_uncompressed_bytes)) AS uncompressed_size,

round(sum(data_uncompressed_bytes) / sum(data_compressed_bytes), 2) AS ratio

FROM system.columns

WHERE (`table` = 'otel_logs_bloom') AND (name = 'Referer')

GROUP BY name

ORDER BY sum(data_compressed_bytes) DESC

┌─name────┬─compressed_size─┬─uncompressed_size─┬─ratio─┐

│ Referer │ 56.16 MiB │ 789.21 MiB │ 14.05 │

└─────────┴─────────────────┴───────────────────┴───────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.018 sec.

SELECT

`table`,

formatReadableSize(data_compressed_bytes) AS compressed_size,

formatReadableSize(data_uncompressed_bytes) AS uncompressed_size

FROM system.data_skipping_indices

WHERE `table` = 'otel_logs_bloom'

┌─table───────────┬─compressed_size─┬─uncompressed_size─┐

│ otel_logs_bloom │ 12.03 MiB │ 12.17 MiB │

└─────────────────┴─────────────────┴───────────────────┘

1 row in set. Elapsed: 0.004 sec.

In the examples above, we can see the secondary bloom filter index is 12MB - almost 5x smaller than the compressed size of the column itself at 56MB.

Bloom filters can require significant tuning. We recommend following the notes here which can be useful in identifying optimal settings. Bloom filters can also be expensive at insert and merge time. Users should evaluate the impact on insert performance prior to adding bloom filters to production.

Further details on secondary skip indices can be found here.

Extracting from maps